Fairness and Organizational Performance: Insights for Supply Chain Management

Introduction >

Theoretical Background >

Fairness and Organizational Performance >

Conclusion >

Works Cited >

Introduction

What you need to know

Fairness is an ethical principle that speaks to how we treat one another in our social and economic interactions. Managers that seek to improve the fairness of relationships between the firm and employees, as well as within the supply chain, may see positive effects on organizational performance. Here is what you need to know:

Fairness is complex and it can be approached from both normative (how we should act) and behavioural (how we do act) perspectives.

To break down the concept, it can be useful to look at fair outcomes, fair processes, and fair interactions.

When employees perceive that they are fairly treated, this can improve their willingness to work hard and collaborate – both key for success.

Fairness in the supply chain can involve navigating large power differences as well as engaging with supplier practices.

To improve supply chain fairness, particularly at the BOP, we need to look beyond outcome fairness and incomes, and to consider how to make processes and interactions fairer.

Abstract

For this briefing document we review the organizational fairness literature with a focus on the supply chain context. Supply chain fairness is an under-researched topic and we seek to close this gap through a systematic literature review. We draw upon key contributions to the psychology, economics and organizations studies literature to illuminate the salient features of fairness in social and economic systems, such as supply chains. This briefing document highlights that fairness influences economic behaviour and firm performance in important ways. The literature shows that fairness in organizational practices can foster various sources competitive advantage and hence improve organizational performance. While there is a robust literature on fairness in the human resources management (HRM) domain, fairness perceptions by other stakeholder groups are underexplored and warrant further research attention. Moreover, while the business case for supply chain fairness is well established, other salient issues remain under-researched in the academic literature. We explore avenues for future research.

Preamble

For this briefing document we review the organizational fairness literature with a particular focus on the supply chain context. Broadly speaking, fairness is a moral intuition and social norm, which has been derived conceptually from philosophy and political theory. Fairness principles are plural (Capellen et al, 2007; Konow, 2003) and values form the basis of fairness judgements (Etzioni, 1988; Schminke et al, 2014). An important insight from this brief is that concerns for fairness fundamentally affect economic behaviour and fairness appears to be significantly related to organizational performance. Most studies of organizational fairness focus on the employees as the focal stakeholder group; we find that other stakeholder contexts, including supply chain relationships, remain under-researched.

We draw upon key contributions to the psychology, economics and organizations studies literature to illuminate the salient features of fairness in supply chains. Organizational fairness has emerged as an important topic in the literature as it has been found that behaviour is not only determined by self-interest; many people are strongly motivated by other-regarding preferences, including concerns for fairness (Kahneman et al, 1986). This has important implications for what is considered a fair profit level, fair wage or fair price in the supply chain context and how such fair allocations can be achieved procedurally. We explore these issues through a systematic review of the literature addressing fairness in the supply chain.

Introduction >

Theoretical Background >

Fairness and Organizational Performance >

Conclusion >

Works Cited >

Theoretical Background

Fairness is concerned with how we treat one another in our social and economic interactions. By invoking fairness, we are making some statement, forming some judgement, about how people ought to be treated, how they are actually treated, and what this implies for justice. The formal principle of distributive justice can be found in Aristotle’s statement of equality that equals should be treated equally and unequals unequally. More precisely:

Individuals who are similar in all respects relevant to the kind of treatment in question should be given similar benefits and burdens, even when they are dissimilar in other irrelevant respects; and individuals who are dissimilar in a relevant respect ought to be treated dissimilarly, in proportion to their dissimilarity (Velasquez 1998).

Since Aristotle, thinking on fairness has continued to develop. Theoretical treatments of fairness from moral and political philosophy now yield a plurality of fairness principles, although many engage core concepts such as equality, equity, need, merit and efficiency. These theoretical approaches to fairness are contrasted in the Summary of Relevant Theoretical Approaches to Fairness, at the end of the section.

Empirical studies of fairness principles in human action indicate that individuals often favour collections of fairness principles, prioritising or combining them according to the context. In a study of fairness trade-offs, Ordonez & Mellers (1993) examine responses to, firstly, what people would favour in the ‘more fair’ society, and, secondly, what they would favour in the society in which they would ‘prefer to live’. They found that ‘people value equity but prefer to live in societies that sacrifice some equity in order to provide for higher minimum and mean earnings’ (Konow, 2003: 1234). In a review of studies of fairness preferences, Konow (2003) concludes:

The implication of these studies is that equity (i.e., justice in the specific sense) guides but does not monopolize distributive preferences: people care about equity, but the allocations they prefer for themselves and consider right are also influenced by concerns for efficiency and need. (ibid: 1235)

This leads Konow (2003) to propose a ‘multicriterion theory of justice’ in which ‘three justice principles are interpreted, weighed and applied in a manner which depends upon the context’ (ibid: 1235). The social processes whereby people collectively determine what fairness means and how fairness principles are to be identified, weighted and prioritised against other moral concerns, leads James (2013) to propose that fairness is a social practice, and a core component of any scheme of ‘mutual assurance’. As a social practice, fairness principles become part of the formation process of fairness perceptions, which includes collective judgements on how people are treated according to the values relevant to the situation (Etzioni, 1988; Schminke et al, 2014). Fairness as a social practice includes the procedural, distributive, interactive dimensions of justice (Whitman et al, 2012).

The effectiveness of social practices in arriving at ‘all things considered’ fair outcomes depends on an integrated set of factors such as setting up the communicative interaction based upon mutual respect, openness and availability of information, readiness to listen to different points of view and commitment to the outcome. In order to be seen to be fair, communicative interactions must adopt systematic procedures for weighing up competing claims and interests. For example, in order to mediate fairly between different kinds of publicly acknowledged and legitimate claims, Griffin (1995) proposes a principle of trade-offs: ‘first, a principle of maximization; and next, when maximization does not rank options, a principle of equal well-being; and finally, when equalization does not rank options, a principle of equal chances at well-being’ (ibid: 104). Anand (2001) found that people view processes that allow for greater participation, freedom and information as more fair. Finally, Frey & Stutzer (2001) argue that fairness as justice is not our sole concern, but that behaviour and preferences may be motivated also by altruism, responsibility, friendship, self- interest or other moral considerations.

Taking a different approach, in his analysis of the etymological origins of ‘fair’, Cupit (2011) traces the links between fairness and social order. Perceptions of fairness indicate what our moral sensibilities find to be pleasing and attractive. In particular, fairness picks out the kinds of reasons that should guide our interactions: ‘To be partial and biased is to be moved by the wrong sorts of reasons’ (ibid: 398). Arrangements may be judged to be orderly, and therefore fair, when allocations are ‘in accordance with what is due’ (ibid: 399), and subject to distributive procedures that are guided by the correct reasons of impartiality and efficiency, according to some publicly recognised feature of the recipient such as need or desert. Such publicly recognised features of fairness ground our capacity to make legitimate claims (Broome, 1994). A claim is a compelling reason that ‘is owned to the candidate herself,’ and fairness aids us in mediating between different kinds of claims.

More specifically, claims do not operate as constraints; rather, ‘fairness requires that each candidate’s claim should be satisfied in proportion to its strength’ (ibid: 38). Therefore the satisfaction of claims is dependent upon a number of factors including: what is judged to be a valid and legitimate claim, the claims of others and the process for judging between different kinds of claims. The potential for proliferation of differences in opinion, judgement and settlement is clear. What rules will guide the determination of fairness, who will be involved, and what will be the basis of their involvement is a necessary part of any ‘fairness system’.

In this way, the social norm of fairness underwrites regularity, impartiality and how to treat other people in non-arbitrary social arrangements, characterised by ‘mutual assurance’ (James, 2013). Mutual assurance is the certainty and security in that we can expect others to act in regular and predictable ways. This assurance and security is vital for mitigating the risks associated with social cooperation, increasing trust and reducing the anxiety that we will be exploited or will fail to secure a fair return from joining our efforts to those of others.

Summary of Relevant Theoretical Approaches to Fairness

General Theories:

Naturalism:

Behavioural economics; evolutionary theory; psychology

Deontology:

Duties and rights

Consequentialism:

Utilitarianism and welfare consequentialism

Social Constructivism:

Sense-making and discourse theory

Gielissen & Graafland (2009):

Egalitarianism:

Equal incomes for all

Positive Rights:

Rights to a minimum income

Principle of moral desert:

Contribution measured by effort or market price

Libertarianism:

Transactions are fair when they are voluntary

Konow (2003):

Need Principle:

Equal satisfaction of basic needs (Rawls, Marx)

Efficiency Principle:

Maximising surplus

Equity (accountability) Principle:

– ‘proportionality and individual responsibility’ (equity and desert theory, Nozick)

Context Family:

– ‘dependence of the justice evaluation on the context, such as the choice of persons and variables, framing effects and issues of process’ (Kahneman, Knetsch & Thaler, Walzer, Elster, Frey).

Cappelen at al. (2007):

Strict Egalitarianism:

All inequalities should be equalised even in cases involving production

Libertarianism:

The fair solution is to give each person what he or she produces

Liberal Egalitarianism:

Only inequalities arising from factors under individual control should be accepted

Key Insights from Economics and Psychology

Behavioural economics has shown that economic behaviour is not only determined by self-interest and that many people are strongly motivated by other-regarding preferences, including fairness. This short summary looks at key insights from survey and experimental research on how and in which situations fairness constraints impact economic transactions.

Cognitive psychologists and behavioural economists have advanced this area of research through survey and experimental design methods. Research has tried to establish fairness rules regarding the distribution of resources among different actors, for example, firm and consumer or firm and employee. These have important implications for what is considered a fair profit level, fair wage or fair price and how such fair allocations can be achieved procedurally. This research suggests that fairness concerns matter more in some markets than others. Generally, self-interest tends to dominate in competitive markets, while other-regarding preferences, including fairness, matter more in markets with incomplete contracts, such as labour markets (Fehr and Schmidt 2001). Indeed, context matters, and it has been suggested that fair-minded people will not always behave “fairly” and that self-interested people will sometimes behave “fairly”, depending on the strategic environment in which transactions take place (Fehr and Schmidt 2001).

Classic studies have looked at how participants perceive outcome fairness; outcome fairness concerns the result of an interaction and is often contrasted with procedural fairness, which concerns the process that lead to an outcome. In their famous survey-based study, Kahneman et al. (1986) introduced the principle of “dual entitlement,” i.e. that both parties to a transaction are entitled to a reasonable amount of gain. The concept of reference transactions tends to be adopted as measure of fairness. A reference transaction is a precedent or yardstick against which other transactions are measured; this could be derived from a recent transaction, for example, or a perceived ‘average’ transaction. Firms are entitled to the profit realised in reference transactions, and stakeholders are entitled to the terms of the transaction. This implies that it is considered fair for firms to raise prices as costs rise (Kahneman et al. 1986; Rubin 2012). Furthermore, it has been shown that people are willing to punish behaviour that is perceived as unfair and are willing to reward actions that are perceived as generous or fair (Fehr, Kirchsteiger and Riedl 1993).

This willingness to punish unfair behaviour has been illustrated in the classic ultimatum game whereby two players have the chance to win a sum of money, which is supposed be split between them. One player makes an offer on how to split the sum; the other player can accept or reject the offer. If the deal is rejected, both players receive nothing. It is has consistently been shown that people tend to be unwilling to accept low, ‘unfair’, offers and prefer sacrificing money to lower the pay-out of the other player (G th, Schmittberger, and Schwarze 1982). Indeed, the Gift Exchange Game has shown that people are willing to reward fair behaviour (Fehr, Kirchsteiger and Riedl 1993). In this game, a proposer offers a sum of money, which a responder can accept or reject. Both players don’t receive any money for a rejected offer. The acceptance of the offer tends to be positively related to the amount of money offered (Fehr and Schmidt 2001). Interestingly, it has been shown that a rise in stake levels does not necessarily induce people to act in a more selfish manner (Fehr and Schmidt 2001; Fehr and Tougareva 1995). In recent years, these mechanisms have been explored further through more complicated experimental set-ups, including repeat experiments (Fehr and Schmidt 2001; Charness and Rabin 2005).

While a large part of the experimental literature has focused on outcome fairness, some studies have also addressed the question how procedures impact perceived fairness. The concept of “procedural utility,” which is defined as the benefits derived from a well-designed process rather than just its outcomes, can shed light on this question. Frey et al. (2004) show that individuals can derive procedural utility from institutional sources and interactions with other actors. For example, people may gain procedural utility from democratic institutions because they voted for their representatives (the process) not simply because the elected officials may be more responsive (the outcome). They may also gain procedural utility if they feel fairly treated by other actors, for example, their employers.

Even though many previous studies did not take an explicit procedural perspective, they have implications for procedural utility and fairness. For example, Kahneman et al.’s (1986) classic study that found that a majority of respondents viewed an increase of the price of snow shovels after a snowstorm unfair has procedural dimensions. Frey et al. (1993) interpreted this to mean that people view using market mechanisms to address excess demand as procedurally unfair. Against this background, the authors designed a survey study where they presented the snowstorm scenario to participants. Respondents considered first-come-first-served and administration-based allocation procedures to be fairer than market-based mechanisms to deal with the excess demand for snow shovels. Other studies have used experiments to determine if procedures affect how as how fairly outcomes are seen. For example, it has been suggested that people tend to be more willing to accept the smaller share of a sum of money if the split was randomly assigned, but they tend to reject “unfair” offers from self-interested players (Blount 1995; Charness 2004).

Finally, an emerging research avenue investigates under what circumstances people are willing to give up some of their own financial gain to reward (or punish) someone who has behaved fairly (or unfairly) to another person (Kahneman et al. 1986; Turillo et al. 2002). This has been interpreted as meaning that “virtue is its own reward.” This line of research has potentially important implications for business life: people might choose to invest in socially responsible companies over socially irresponsible companies or buy from socially responsible companies rather than socially irresponsible companies as a means of ‘rewarding’ fair behaviour (Turillo et al. 2002).

Introduction >

Theoretical Background >

Fairness and Organizational Performance >

Conclusion >

Works Cited >

Fairness and Organizational Performance

While the studies described above suggests how and why perceived fairness influences the behaviour of consumers, employees and other company stakeholders, few studies focus directly on the link between fairness and organizational performance, as measured by financial performance, which reflects difficulties with research design (Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005). However, a significant number of research papers have been able to address the related question of whether or not fairness is a source of competitive advantage. Overall, these papers do find that fairness can play a key role in building sustained competitive advantage, namely by affecting how firms manage human resources, knowledge, leadership, and innovation, as well as how fairness shapes supply chain management, operations management, and drives social and environmental performance.

The following sub-sections focus on the influence of fairness on relationships with employees, stakeholders in the supply chain, and, more specifically, stakeholders in an agricultural supply chain. In exploring these relationships, we describe how affecting perceived fairness in these relationships can benefit both the corporation and the other party. While not discussed in depth in this review, it has been hypothesized that fairness perceptions of non-employee stakeholder groups lead to similar behavioural and attitudinal changes and associated organizational performance implications. Bosse et al. (2009) argue that the level of contribution non-employee stakeholders provide to the firm varies according to their perceptions of reciprocity determined by perceptions of fairness. Against this background, it can be assumed that stakeholder relations based on principles of distributional, procedural, and interactional justice can unlock potential for value creation (Harrison et al. 2010).

Fairness and Employees

Most organizational research has focused on employee reactions to fairness and justice (or injustice) in organizational practices (Heslin and VandeWalle 2011; Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005; Cropanzano et al. 2001; Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001). As Konovsky (2000: 500) notes: “Nowhere are the practical implications of PJ [procedural justice] research so evident as in the human resources management arena.” It has been found that fairness of organizational policies can lead to the following:

Individual attitude adjustments (Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005)

Organizational citizenship behaviours (OCBs, Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005)

Changes to individual (team) work and job performance (Aryee et al. 2004; Zapata-Phelan 2009; Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001)

Research has confirmed that each of these outcomes can enhance organizational performance (Podsakoff and MacKenzie 1997; Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005). Furthermore, insights from the extensive research on fairness and employees can potentially be applied to other stakeholder groups (Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005).

Cropanzano et al. (2001) suggest three reasons why employees care about fairness (1) instrumental, fairness as a means to an end, (2) interpersonal, fairness as underpinning interpersonal relationships, and (3) moral, fairness as upholding moral principles. Four key areas of interest are fairness in selection, compensation, performance evaluation, and drug testing (Konovsky 2000). Overall, organizational fairness seems to promote employee well-being and, as summarised above, organizational performance (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001). Key meta- reviews (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001; Colquitt et al. 2001) find strong correlations between distributive fairness and outcome satisfaction, job satisfaction, trust, and affective commitment. Similarly, the studies find strong correlations between procedural justice and outcome satisfaction, job satisfaction, trust and organizational commitment, as well as interactional justice and job satisfaction (Nowakowski and Conlon 2005). Nowakowski and Conlon (2005) highlight the importance of considering contextual fairness moderators, including industry norms, cultural norms, organizational structure, and role definitions, as well as individual level moderators, including work experience, self-efficiency, gender, protected group status, and personality.

In addition, research has shown that fairness can help mediate common conflicts between organizations and employees regarding knowledge and improve knowledge management and information sharing, both of which are considered important sources of competitive advantage. It has been shown that fairness in decision-making, recognition and reward can foster a knowledge sharing culture (Hislop 2003; Flood et al. 2001). Stakeholders tend to be more willing to share information regarding their utility functions or preferences when treated fairly, which can spur innovation and allow the firm to deal better with changes in the environment (Harrison et al. 2010).

In this sense, fairness in organizational practices can encourage voluntary cooperation (Kim and Mauborgne 1998; Rechberg and Seyd 2013). In contrast, perceived lack of fairness in organizational practices can lead to “hoarding” of ideas (Kim and Mauborgne 1998).

Similarly, fairness has also been shown to matter in a variety of innovation contexts, as it is an antecedent of trust, which fosters partnership and cooperation, required for innovation (Bstieler 2006). Fairness can enhance both intra- and inter-organizational innovation. For the intra- organizational context it has been suggested that perception of procedural and outcome fairness enhanced the acceptance of innovations by change recipients, for example employees (Jiao and Zhao 2014). Furthermore, cross-functional fairness can foster innovation in product innovation teams (Clercq 2013; Qiu 2010). Fairness perceptions can also encourage the participation in inter- organizational and open innovation (Garriga et al. 2012; Zablah 2005; Van Burg et al. 2013). A key insight for inter-organizational innovation is that collaboration in innovation activities is not just influenced by material incentives, but also by social preferences such as fairness (Gachter et al. 2010).

Implementing organizational fairness is not always straightforward or intuitive for organizations. For example, research has demonstrated that a “justice dilemma” exists regarding selection tools (Konovsky 2000). For example, applicants often regard unstructured interviews as more fair, even though research has demonstrated that structured interviews tend to be more accurate (Latham and Finnegan 1993). A full discussion of how organizational structures and managerial practices can be modified to increase fairness and the barriers to making these changes is, unfortunately, beyond the scope of this briefing.

Fairness in the Supply Chain

Early research on organizational fairness looked at employees as the focal stakeholder group (Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005). In recent years, researchers have become increasingly concerned with the topic of supply chain fairness. Fairness in supply chains is an important and interesting research topic because supply chain partners are often in different positions of power, which exposes the weaker party to vulnerabilities (Duffy et al. 2013; Kumar 1996). As will be discussed in the next sub-section, this is of particular relevance to supply chain relationships that span the global North and South.

Three dimensions of supply chain fairness are frequently considered in the literature. The first dimension, distributive fairness, concerns the key questions of whether benefits and burdens are fairly shared among supply chain partners (Kumar 1996). The second dimension, procedural fairness, looks at decision-making processes in the supply chain. An important concern is whether all supply chain partners have a voice in decision-making. Do large buyers simply inform their suppliers about prices, standards and buying decisions or do suppliers have a true say in the negotiation process? Participation in decision-making is of particular importance because more powerful supply chain partners might not always be aware of the conditions under which more vulnerable supply chain partners operate (Duffy et al. 2013; Kumar 1996). The third dimension, interactional fairness, concerns the communication progress. Supply chain fairness implies that communication between partners is open and that procedures are in place to manage conflicts (Narasimhan 2013).

There is a strong, emerging literature on the business case for supply chain fairness. This area of research mirrors the vast literature focusing on employee-related fairness, as highlighted above, by looking at the relationship between fairness and in-role and extra-role behaviour. Many influential studies have focused on developed countries or emerging markets such as China (see Overview of Key Articles on Supply Chain Fairness); these have found that distributive and procedural justice can both limit the extent of conflict in supply chain relationships and encourage compliance (Brown et al. 2006).

Fairness can also have a significant impact on social elements of supply chain relationships, which are often not contractually specified (Griffith et al. 2006). It has been shown that if one supply chain member treats its partner fairly, specifically in terms of processes and reward allocation, its partner reciprocates by adopting attitudes and engaging in behaviours aimed at strengthening the partnership (Griffith et al. 2006). Similarly, it has been suggested that fairness can influence attitudinal and behavioural outcomes such as long-term orientation, trust and relational behaviour. These can have important influence on relationship performance (Griffith et al. 2006). Supply chain fairness can also encourage partners to engage in behaviours that are over and above that which is formally expected within the terms of supply (Duffy et al. 2013; Kashyap and Sivadas 2012). For example, suppliers who feel fairly treated by key retail customers were more likely to invest resources in the acquisition and use of data central to a retailer’s CRM strategy (Duffy et al. 2013).

Overview of Key Articles on Supply Chain Fairness

Author – Brown et al. 2005:

Fairness measurement – Rewards, consistency, voice, bilateral communication

Context – U.S.

Method – Survey

Author – Duffy et al. 2013:

Fairness measurement – Price, payment terms, costs, bilateral communication, treatment compared to other

suppliers, policies to resolve conflicts, provision of information, familiarity with conditions, mutual respect

Context – U.K.

Method – Semi-structured interviews

Author – Griffith et al. 2006:

Fairness measurement – Fair treatment (general), ability to contribute to exchange relationship, outcomes/ rewards, long- term orientation, bilateral communication, specific issues (credit terms, pricing issues etc.)

Context – U.S.

Method – Survey

Author – Gu and Wang 2011:

Fairness measurement – Profit allocation, treatment compared with other suppliers, respect

Context – Hong Kong

Method – Survey

Author – Kashyap and Sivadas 2012:

Fairness measurement – Rewards, procedures and policies, respect

Context – U.S.

Method – Survey

Author – Liu et al. 2012:

Fairness measurement – Rewards, consistency of procedures, respect, open communication

Context – China

Method – Survey

Author – Narasimhan et al. 2013:

Fairness measurement – Governance decisions, rewards, openness in communication

Context – U.S.

Method – Survey

Supply Chain Fairness at the BOP

As shown above, the focus of the supply chain fairness literature has been on establishing a business case for fairness. While this extends the discussion of fairness beyond the human resources management (HRM) context, this literature leaves a number of questions unanswered. What about supply chain relationships involving partners in developing countries? Distributors, producers and farmers in the South often operate on a smaller scale than their equivalents in the North, which makes fairness concerns even more pertinent. And what about fairness considerations for workers that are being employed in the supply chain? Key issues presented by supply chains extending to developing countries and involving very small suppliers remain under- studied. Very small suppliers, producers, and distributors, in particular in the South, face specific challenges and are often vulnerable. Base of the Pyramid (BOP) producers and distributors often face challenges regarding access to a fair debt market, insurance, technology and expertise. Furthermore, relationships with intermediaries are often problematic (London et al. 2012).

Few articles on supply chain fairness have studied these contexts. However, the fair trade literature can offer some insights. It should be noted that most fair trade research does not explicitly conceptualize fairness or how a fair price should be calculated. Indeed, price fairness judgments concern both the outcome and the procedure leading to the outcome (Nguyen and Meng 2013). It should be noted that there is a large literature on price fairness for consumers and that this could be an important resource for exploring price fairness in supply chain relations. According to the consumer literature, important factors include transparency, honesty, reliability, influence and a say in decisions, consideration, respectfulness and consistent behaviour (Diller 2000). Against this background it is not surprising that it has been suggested that fair price in the supply chain “covers all production costs for the goods, including environmental and social costs, provides a decent standard of living for the producers with something left over for investment” (B ji-B cheur et al. 2008).

Research into fair trade arrangements has highlighted that bilateral communication (B ji-B cheur et al. 2008), fair and guaranteed price (B ji-B cheur et al. 2008; Moore 2004), advance payments (Moore 2004), and sustainable, long-term relationships (B ji-B cheur et al. 2008) are important for building “fair” fair trade partnerships. These characteristics are similar to the fairness perceptions identified in general supply chain fairness research. However, vulnerable exchange partners in fair trade situations tend to enjoy a significantly higher degree of protection and more favourable trading terms. Some studies have addressed the question how “fair” fair trade is in reality. Most fair trade schemes guarantee a minimum price to fair trade organizations but it is unclear if producers actually receive the minimum price (Weber 2007). Furthermore, many fair trade schemes specify that fair trade organizations have to pay a living wage to employees – but what about seasonal workers hired directly by producers (Weber 2007)? It should also be noted that while fair trade has increasingly been mainstreamed, it remains a premium, niche-market approach.

Most studies have asked how fairly suppliers feel that they are being treated. But these questions only scratch the surface: as noted above, what if a supplier does not treat its own employees fairly? This shows that supply chain fairness is a complex and multifaceted issue that also includes questions related to concerns such as living wages, child labour and working conditions. Large buyers have started to take responsibility for fairness in their supply chains beyond paying a fair price. This extended notion of supply chain fairness implies that suppliers make attempts to ensure decent working conditions, labour rights, living wages, and address child labour (Boyd et al. 2007; Tallontire and Vorley 2005). It widely accepted that a living wage is higher than national minimum wage in many countries but there is no agreement on how a living wage should be calculated in practice (Miller and Williams 2009). A living wage implies that all workers should earn a wage adequate purchase goods and services necessary to support and sustain their dignity (Figart 2001). Importantly, a living wage takes the approach that full-time work should be enough to support a family. It should be noted that living conditions and family arrangements vary across developed and developing countries which might make it difficult to compare living wages across countries.

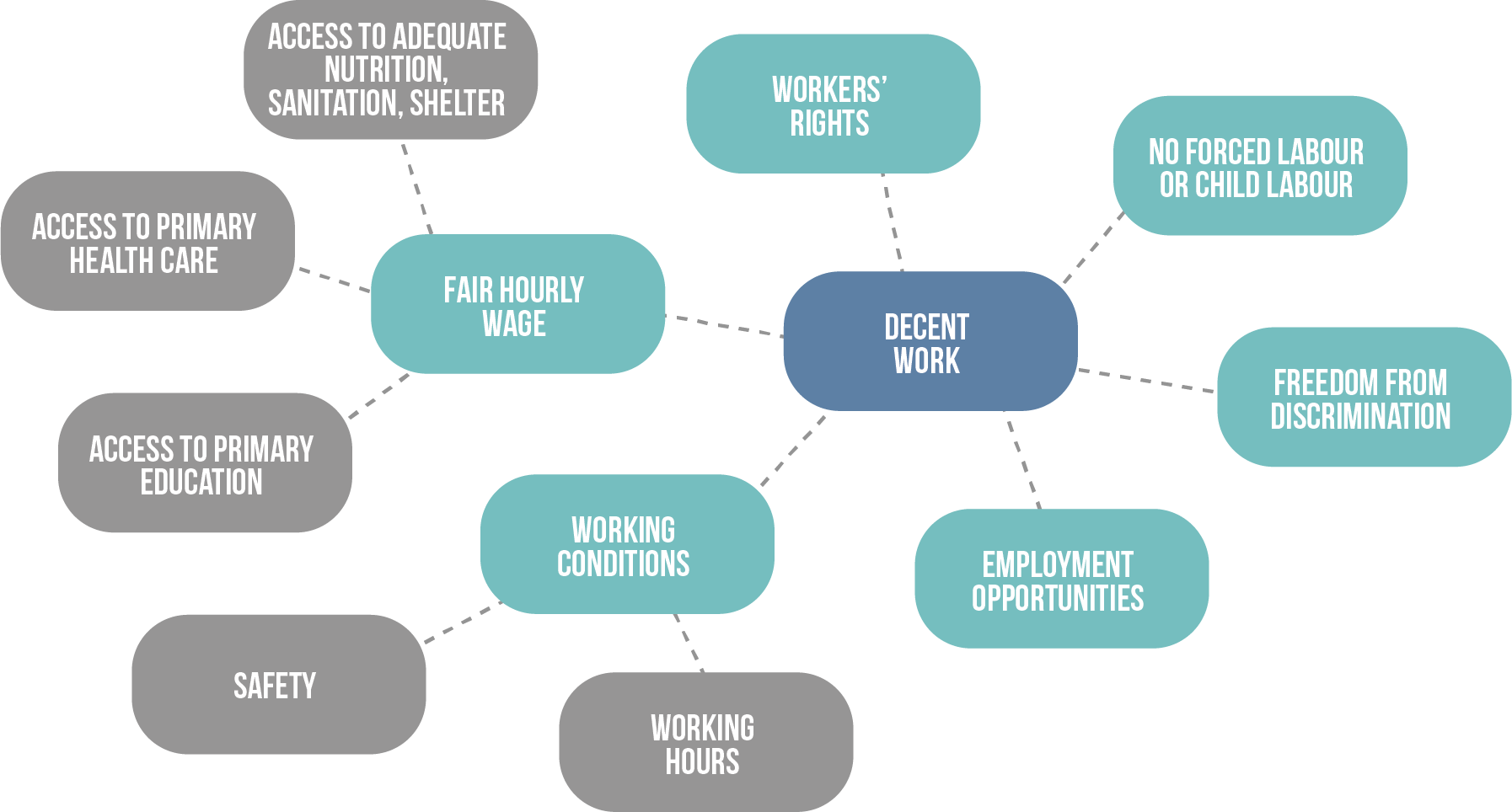

The ILO framework on decent work goes beyond the idea of a living wage and provides a comprehensive summary of factors that can contribute to fair treatment of workers (see Figure I). This is potentially helpful to establish what fair treatment of workers implies for the developing country context. Importantly, it has been suggested that supply chain fairness has to go beyond monitoring and compliance approaches regarding the promotion of living wages and decent work and be based on communication and partnership (Boyd et al. 2007). Strategies characterized by procedural justice rather than by greater monitoring are more likely to increase supplier compliance without damaging a buyer’s exchange relationships with their suppliers (Boyd et al. 2007).

Figure I: Decent Work Framework

Based on Dharam (2003)

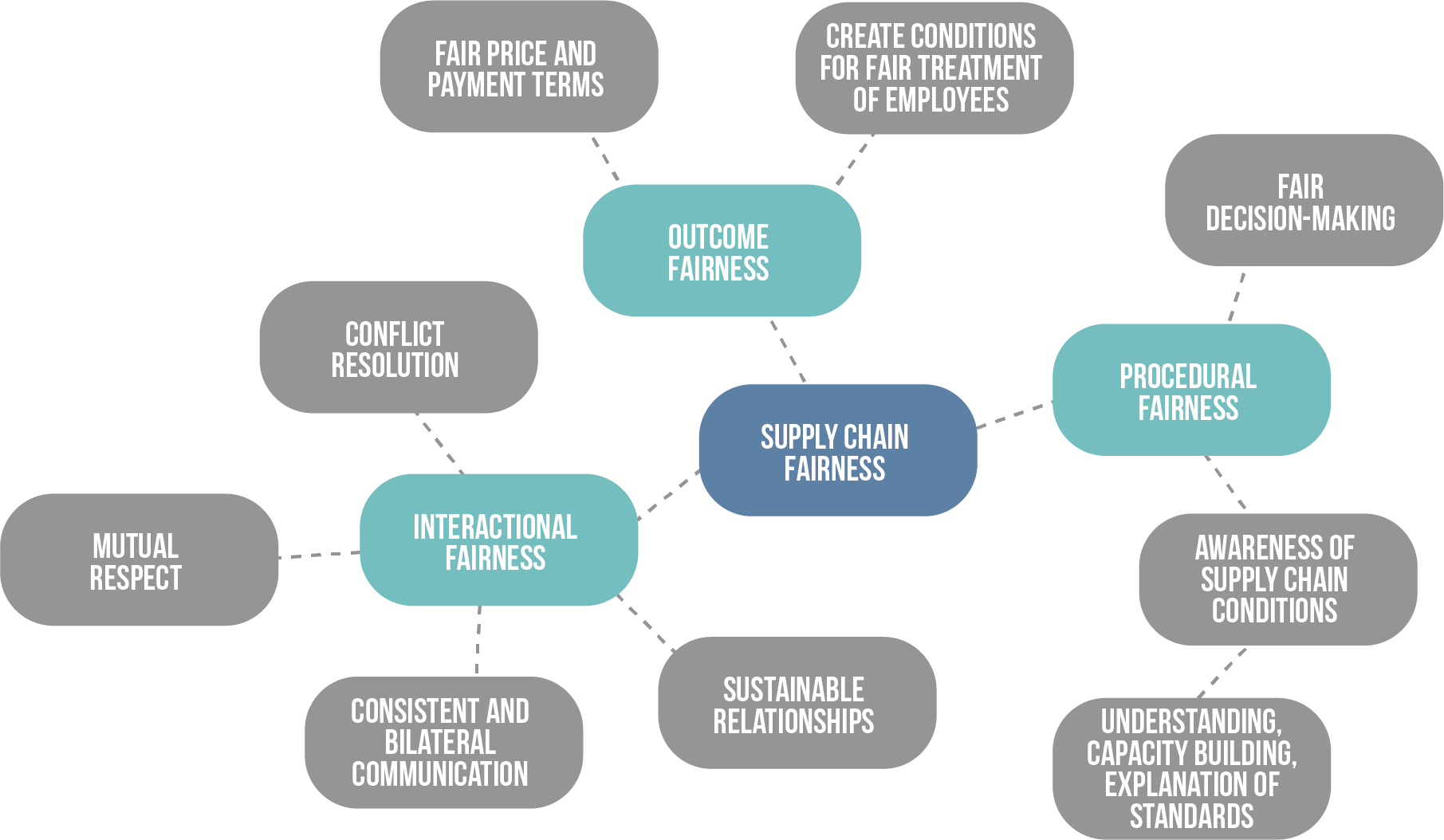

Building on the multi-dimensional nature of the ILO framework, for the Bottom-of-the-Pyramid (BOP) context Ansari et al. (2012) and others suggested that supply chain relationships could be improved by fostering capability development. This approach asserts that supply chain fairness has to look beyond increasing incomes to focus on increasing human capital. In this sense, a capability development approach goes beyond the traditional fair trade model. It includes important groups such as small distributors, traditionally not involved in fair trade schemes and provides new opportunities for engaging in novel forms of supply chain fairness.

Figure II, below, brings together Ansari’s expanded view of supply chain relationships at the BOP with the fairness literature to provide a new model for conceptualising and mapping supply chain fairness. The diagram provides an overview how outcome fairness, interactional fairness and procedural fairness can inform supply chain design. It illustrates that supply chain fairness is complex and multifaceted, and should not be reduced to a narrow focus on incomes. As the diagram illustrates, incomes are but one element of outcome fairness and sit alongside concerns with decision-making procedures and mutual respect. The issues described in Figure II become particularly pertinent when thinking about supply chain fairness at the BOP. These are the building blocks of fairer supply chains.

Figure II: Overview of Supply Chain Fairness

When considering supply chain fairness at the BOP, it is particularly important to consider smallholder farmers. Agricultural markets are subject to price volatility, impact of severe weather, and imbalances of power between producers and buyers are often found (Hellberg-Bahr and Spiller 2012; Tallontire and Vorley 2005). This makes fairness concerns particularly pertinent. Smallholder farmers face numerous challenges regarding the participation in national or global value chains, including, lack of information of market opportunities, lack of access to capital, inputs, technologies, dependence on intermediaries, and lack of institutional support (Salami 2010; Zylberberg 2013). Given these constraints, smallholders often cannot achieve the scale of production necessary to participate in national or global markets (Hussein 2001). A common way of linking smallholders to markets is by providing links with consolidators but it is doubtful that this model by itself offers fair prices and trading conditions to farmers.

Scholars highlight the importance of collective action in enhancing market participation of smallholder farmers, and producer organizations are important for supporting smallholder farmers. The literature has distinguished between different types of producer organizations. The most common form of producer organizations is the agricultural cooperative. Cooperatives are collectively owned enterprises and their formation is often promoted through governments in developing countries (Wanyama et al. 2014). However, government interference has been cited as a key obstacle to cooperative success (Shiferaw et al. 2009). In the aftermath of agricultural market liberalisation policies government-promoted cooperatives lost part of their influence but continue to be important, often in restructured forms. With the decline of government-promoted cooperatives, NGOs and other donor organizations have started to support farmers’ producer organizations (Onumah et al. 2007; Wanyama et al. 2014; Shiferaw et al. 2009).

Federations of cooperatives or producer organizations often engage in lobbying to promote farmers’ interests at the institutional level (Onumah et al. 2007). Key benefits of producer organizations are to enhance access to information, capital and technology, reduce transaction costs, enhance economies of scale, improve bargaining power and provide services to members including, marketing and capacity development (Fayet and Vermeulen 2012; Markelova and Mwangi 2010).

Research often focuses on the economic empowerment function of agricultural producer organizations. However, it is not sufficiently emphasised that this economic empowerment results from joining and amplifying farmers’ voices – a key element of procedural and interactive fairness. In a wider sense, they can be regarded as organizations regulating the relations between farmers and external economic, institutional and political environment. Research has pointed to the advocacy function of federations of producer organizations. In this sense, producer organizations can have a grassroots democratic function (Hussein 2001). However, it should not be forgotten that member representation is not always efficient in producer organizations (Mercoiret and Mfou’ou 2006).

It has been argued that governance structures of producer organizations have to be strengthened to ensure that individual farmers have a voice. For the Fairtrade context, Dolan (2010: 34) noted that producers often don’t have a voice and that “patronage and exclusion” can frequently be found. In particular, minority groups are often underrepresented in producer groups and special efforts need to be made to give a voice to female farmers. Cultural gender awareness is important to improve participation of female farmers in collective groups (Quisumbing and Pandolfelli 2010).

As multinational buyers seek to implement fair relationships with smallholder farmers, producer groups and NGOs can play a key role. There is an opportunity to promote fairness in innovative ways by fostering inclusive procedural fairness. It is not just important to include producer organizations in decision-making but to promote deliberation among stakeholders, involvement of minorities in discussions and capacity development on the ground level. For this purpose it has been suggested that producers should ideally be governed by principles of collaborative governance, allowing for representation and deliberation (Sutton 2013). One way of achieving this ambitious aim could be to work with proactive NGOs and producer organizations that make representation of small producers and minorities, as well as deliberation, their aims (Sutton 2013).

Introduction >

Theoretical Background >

Fairness and Organizational Performance >

Conclusion >

Works Cited >

Conclusion

This briefing document highlights that fairness concerns influence economic behaviour and firm performance in important ways. The literature shows that fairness in organizational practices can foster various sources competitive advantage and hence improve organizational performance. This is an important insight, and adds to the body of evidence supporting that responsible and ethical practices can produce better outcomes for all involved. By returning to the philosophical and behavioural roots of fairness, this briefing provides a foundation for understanding fairness, which can be used to inform and evaluate organizational practices, particularly regarding supply chain management.

While there is a robust literature on fairness in the HRM domain, fairness perceptions by other stakeholder groups are underexplored and warrant further research attention. More specifically, this briefing paper argued that fairness in supply chains is an important research topic: supply chain partners are often in different positions of power, which exposes the weaker party to vulnerabilities. There is considerable scope for expanding our understanding of fair interactions in the supply chain beyond income. The new model for supply chain fairness presented in this paper highlights three dimensions of fairness, and we find that these dimensions are useful for thinking about criteria for fair treatment of supply chain partners.

In addition, other salient issues remain under-researched in the academic literature on supply chain fairness. Open questions concern how fairness principles can be implemented when very small-scale, vulnerable producers are involved. Furthermore, supply chain fairness implies not only fair treatment of suppliers but also fair treatment of workers within the supply chain. This additional layer of supply chain fairness remains largely unexplored in the literature. In particular, the study of voice should be extended beyond employees as stakeholders. While research on supply chain fairness has highlighted the importance of procedural fairness, the issue of voice is rarely discussed explicitly. Future research would benefit from studying how multi-stakeholder governance and deliberation can provide voice to suppliers and intermediaries, including trade unions, cooperatives and NGOs and the effect on fairness perceptions.

Introduction >

Theoretical Background >

Fairness and Organizational Performance >

Conclusion >

Works Cited >

Works Cited

Ansari, S., Munir, K., and Gregg, T. (2012). Impact at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’: the role of social capital in capability development and community empowerment. Journal of Management Studies 49(4), 813-842.

Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., & Budhwar, P. S. (2004). Exchange fairness and employee performance: An examination of the relationship between organizational politics and procedural justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94, 1–14.

Blount, S. (1995). When social outcomes aren’t fair: The effect of causal attributions on preferences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 63(2), 131-144.

Bosse, D. A., Phillips, R. A., & Harrison, J. S. (2009). Stakeholders, reciprocity, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30, 447–456.

Boyd, D. E., Spekman, R. E., Kamauff, J. W., & Werhane, P. (2007). Corporate Social Responsibility in Global Supply Chains: A Procedural Justice Perspective. Long Range Planning, 40(3), 341–356.

Brown, J. R., Cobb, A. T., & Lusch, R. F. (2006). The roles played by interorganizational contracts and justice in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Business Research, 59(2), 166–175. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.04.004

Bstieler, L. (2006). Trust formation in collaborative new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23, 56–72.

Broome, J. (1994) Fairness versus Doing the Most Good. The Hastings Center Report, 24, 36–39.

Cappelen, A. W., Hole, A. D., Sørensen, E. Ø., and Tungodden, B. (2007). The Pluralism of Fairness Ideals : An Experimental Approach. The American Economic Review, 97, 818–827.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2005). Expressed preferences and behavior in experimental games. Games and Economic Behavior, 53(2), 151-169.

Charness, G. (2004). Attribution and reciprocity in an experimental labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(3), 665-688.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 278–321.

Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z. S., Bobocel, D. R., & Rupp, D. E. (2001). Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 164–209.

Cupit, G. (2011) Fairness as Order: A Grammatical and Etymological Prolegomenon. J. Value Inq. 45, 389–401.

De Clercq, D., Thongpapanl, N., & Dimov, D. (2013). Getting More from Cross-Functional Fairness and Product Innovativeness: Contingency Effects of Internal Resource and Conflict Management. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30, 56–69.

Diller, H. (2008). Price fairness. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 17(5), 353-355.

Dolan, C.S. (2010). Fractured ties. In Lyon, S. and Moberg, M. (Eds), Fair Trade and Social Justice: Global Ethnographies, NYU Press, New York, NY.

Duffy, R., Fearne, A., Hornibrook, S., Hutchinson, K., & Reid, A. (2013). Engaging suppliers in CRM: The role of justice in buyer–supplier relationships. International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 20–27.

Fayet, L., & Vermeulen, W. J. V. (2012). Supporting Smallholders to Access Sustainable Supply Chains: Lessons from the Indian Cotton Supply Chain. Sustainable Development, n/a–n/a.

Fehr, E., & Tougareva, E. (1995). Do competitive markets with high stakes remove reciprocal fairness? Experimental evidence from Russia (pp. 615-692). Working Paper, Institute for Empirical Economic Research, University of Zürich.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (2001). Theories of fairness and reciprocity-evidence and economic applications. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 2703. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=264344

Fehr, E., Kirchsteiger, G., & Riedl, A. (1993) Does fairness prevent market clearing? An experimental investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(2), 437-459.

Figart, D. (2001). Ethical foundations of the contemporary living wage movement. International Journal of Social Economics, 28(10/11/12), 800-814.

Flood, P. C., Turner, T., Ramamoorthy, N., & Pearson, J. (2001). Causes and consequences of psychological contracts among knowledge workers in the high technology and financial services industries. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12, 1152–1165.

Frey, B., & Pommerehne, W. (1993) On the fairness of pricing—an empirical survey among the general population. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 20(3), 295-307.

Frey, B., Benz, M., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Introducing procedural utility: Not only what, but also how matters. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 160(3), 377-401.

Gachter, S., von Krogh, G., & Haefliger, S. (2010). Initiating private-collective innovation: The fragility of knowledge sharing. Research Policy, 39, 893–906.

Garriga, H., Aksuyek, E., Hacklin, F., & von Krogh, G. (2012). Exploring social preferences in private-collective innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 24, 113–127.

Gielissen, R., & Graafland, J. (2009). Concepts of price fairness: empirical research into the Dutch coffee market. Business Ethics-a European Review, 18, 165–178.

Griffith, D. A., Harvey, M. G., & Lusch, R. F. (2006). Social exchange in supply chain relationships: The resulting benefits of procedural and distributive justice. Journal of Operations Management, 24(2), 85–98.

Gu, F. F., & Wang, D. T. (2011). The role of program fairness in asymmetrical channel relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(8), 1368-1376.

Hellberg-Bahr, A., & Spiller, A. (2012). How to Treat Farmers Fairly? Results of a Farmer Survey. International Food & Agribusiness Management Review, 15(3), 87–97.

Heslin, P. A., & VandeWalle, D. (2011). Performance Appraisal Procedural Justice: The Role of a Manager’s Implicit Person Theory. Journal of Management, 37, 1694–1718.

Hislop, D. (2003). Linking human resource management and knowledge management via commitment: A review and research agenda. Employee relations, 25(2), 182-202.

Hosmer, L. R. T., & Kiewitz, C. (2005). Organizational justice: A behavioral science concept with critical implications for business ethics and stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 15, 67– 91.

Hussein, K. (2001). Producer Organizations and Agricultural Technology in West Africa: Institutions that give farmers a voice. Development, 44(4), 61–66.

James, A. (2012). Fairness in Practice: A Social Contract for a Global Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jiao, H., & Zhao, G. Z. (2014). When Will Employees Embrace Managers’ Technological Innovations? The Mediating Effects of Employees’ Perceptions of Fairness on Their Willingness to Accept Change and its Legitimacy. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31, 780–798.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1986) Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. The American Economic Review, 76(4), 728-741.

Kashyap, V., & Sivadas, E. (2012). An exploratory examination of shared values in channel relationships. Journal of Business Research, 65, 586–593.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (1998). Procedural justice, strategic decision making, and the knowledge economy. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 323–338.

Konovsky, M. A. (2000). Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 489-511.

Konow, J. (2003) Which is the fairest one of all? A positive analysis of justice theories.” Journal of Economic Literature, 41(4), 1188-1239.

Kumar, N. (1996). The power of trust in manufacturer-retailer relationships. Harvard Business Review, 74(6), 92.

Latham, G. P., & Finnegan, B. J. (1993). Perceived practicality of unstructured, patterned, and situational interviews. Personnel selection and assessment: Individual and organizational perspectives, 41-55.

Liu, Y., Huang, Y., Luo, Y. D., & Zhao, Y. (2012). How does justice matter in achieving buyer-supplier relationship performance? Journal of Operations Management, 30, 355–367.

Markelova, H., & Mwangi, E. (2010). Collective action for smallholder market access: Evidence and implications for Africa. Review of Policy Research, 27(5), 621–640.

Mercoiret, M. R., & Mfou’ou, J. M. (2006). Rural Producer Organizations (RPOs), Empowerment of farmers and results of collective action. Rural Producers Organizations for Pro-poor Sustainable Agricultural Development.

Miller, D., & Williams, P. (2009). What price a living wage? Implementation issues in the quest for decent wages in the global apparel sector. Global Social Policy, 9(1), 99-125.

Moore, G. (2004). The Fair Trade movement: parameters, issues and future research. Journal of business ethics, 53(1-2), 73-86.

Narasimhan, R., Narayanan, S., & Srinivasan, R. (2013). An Investigation of Justice in supply chain relationships and their performance impact. Journal of Operations Management, 31, 236– 247.

Nguyen, A., & Meng, J. (2013). Whether and to What Extent Consumers Demand Fair Pricing Behavior for Its Own Sake. Journal of business ethics, 114(3), 529-547.

Nowakowski, J. M., & Conlon, D. E. (2005). Organizational justice: Looking back, looking forward. International Journal of Conflict Management, 16(1), 4-29.

Onumah, G. E., Davis, J. R., Kleih, U., & Proctor, F. J. (2007). Empowering Smallholder Farmers in Markets: Changing Agricultural Marketing Systems and Innovative Responses by Producer Organizations. Africa, (September), 37. Retrieved from http://www.esfim.org/esfim/documents/

Phillips, R. (1997). Stakeholder theory and a principle of fairness. Business Ethics Quarterly, 7(1), 51-66.

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Impact of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: A review and suggestions for future research. Human Performance, 10, 133–151.

Qiu, T. J., Qualls, W., Bohlmann, J., & Rupp, D. E. (2009). The Effect of Interactional Fairness on the Performance of Cross-Functional Product Development Teams: A Multilevel Mediated Model. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26, 173–187.

Quisumbing, A. R., & Pandolfelli, L. (2010). Promising Approaches to Address the Needs of Poor Female Farmers: Resources, Constraints, and Interventions. World Development, 38(4), 581–592.

Rechberg, I., & Syed, J. (2013). Ethical issues in knowledge management: conflict of knowledge ownership. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17, 828–847.

Rubin, J. (2012). Fairness in business: Does it matter, and what does it mean? Business Horizons, 55(1), 11-15.

Salami, A., Kamara, A. B., Brixiova, Z., & Bank, A. D. (2010). Smallholder Agriculture in East Africa: Trends, Constraints and Opportunities. Working Paper No.105, (April).

Shiferaw, B., Obare, G., Muricho, G., & Silim, S. (2009). Leveraging institutions for collective action to improve markets for smallholder producers in less-favored areas. Afjare, 3(1), 1–18.

Sutton, S. (2013). Fairtrade governance and producer voices: stronger or silent? Social Enterprise Journal, 9(1), 73-87.

Turillo, C., Folger, R., Lavelle, J. J., Umphress, E. E., & Gee, J. O. (2002). Is virtue its own reward? Self-sacrificial decisions for the sake of fairness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89(1), 839-865.

Van Burg, E., Gilsing, V. A., Reymen, I., & Romme, A. G. L. (2013). The Formation of Fairness Perceptions in the Cooperation between Entrepreneurs and Universities. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30, 677–694.

Velasquez, M.G. (1998). Business Ethics: Concepts and Cases. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Wanyama, F., Poulton, C., Markelova, H., Dutilly, C., Hendrikse, G., Bijman, J., Wouterse, F. (2014). Collective action among African smallholders: trends and lessons for future development. Thematic Research Note 05, (March).

Zablah, A. R., Johnston, W. J., & Bellenger, D. N. (2005). Transforming partner relationships through technological innovation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 20, 355–363.

Zapata-Phelan, C. P., Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & Livingston, B. (2009). Procedural justice, interactional justice, and task performance: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 93–105.

Zylberberg, E. (2013). Bloom or bust? A global value chain approach to smallholder flower production in Kenya. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 3(1), 4–26.

PDF Version

Available to download.

About This Paper

First published 11 November 2016 by the Mutuality in Business Research Team. The web text is based on the paper written by researchers at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. The views of the authors and/or the University from are distinct from other content on this website.

Authors

Dr Ruth Yeoman – Research Fellow at Kellogg College, University of Oxford where she manages the Centre for Mutual & Employee-owned Business. Dr Milena Mueller Santos – holds a DPhil in Organizational Studies from Oxford University.

Authors’ Note

The conclusions and recommendations of any Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Please note: The header photograph is illustrative and does not directly portray the subject matter. Some editorial changes have occurred during the process of converting the paper from the PDF version above into this web page version.

Other Articles

Asia Economics of Mutuality Forum 24-25 April 2024

Korean and global leaders in business, academia, government, and civil society will gather at Hanyang University in Seoul, South Korea, to launch the inaugural Economics of Mutuality Foundation and Hanyang University’s Global Forum on the role of business and investing in society. The event will take place from April 24 to 25, 2024. The two-day event will include addresses by Professor Colin Mayer, former Dean of Oxford University’s Said Business School; Chairman Moon Kook Hyun, President of the New Paradigm Institute and former CEO of Yuhan-Kimberly, and Dr. Jay Jakub, the Executive Director of the Economics of Mutuality Foundation, and co-author of the book, “Completing Capitalism.” The event will highlight the roles of academia, corporations, investors, family offices and entrepreneurs in creating an ecosystem of mutual value co-creation by how companies deploy their capital in society.

Oxford Virtual Executive Education Program 2 May – 20 June 2024

Driving Impact Through Mutual Value Creation, an 8-week online course brought to you by Oxford University’s Saïd Business School and the Economics of Mutuality team, will equip you to walk the talk of Stakeholder Capitalism.

Nordic Economics of Mutuality Forum October 15-16

The first Economics of Mutuality forum to be held in Scandinavia, this event taking place October 15-16, 2024 will be hosted by Brandinnova, the Center for Brand Research at the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH), Jæren Sparebank, and the Economics of Mutuality Foundation.

How Witnessing an Economy of Greed Led Me to Pursue an Economy of Good

Tony Soh is CEO of the National Volunteer & Philanthropy Centre (NVPC) in Singapore. In this interview, he tells us how his experience of the global financial crisis led him to search for better ways of doing business. A graduate of the Oxford Economics of Mutuality Virtual Executive Education Program, he is working to build a movement around corporate purpose in his city